Recent Hub findings, discussed at an international workshop in Uganda, support an integrated antibiotic stewardship framework which understands why farmers make the decisions they do.

A major challenge for tackling excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics in agriculture is understanding and addressing how these drugs are accessed. The sale of antibiotics is often insufficiently regulated and existing restrictions may just as well be hard to enforce.

This is especially the case in places with limited healthcare and veterinary services where people rely on informal providers. Operators of drug stores and other informal providers that are not supposed to sell antibiotics are less likely to know about appropriate use of antibiotics and the risks and dangers of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Similarly, farmers can easily see the apparent benefits of using antibiotics – for treatment, prophylaxis or growth promotion in their livestock – but are often unaware of the risks. The combination of easy access to antibiotics and limited knowledge of providers and farmers of the associated risks has normalised their use and creates the perfect conditions to breed antimicrobial resistance.

This is of critical importance because a major concern for the increase of AMR is the use of antibiotics in agriculture. The World Health Organization has declared AMR as one the top 10 global public health threats.

A GCRF cluster project to address antibiotic stewardship in agricultural communities, led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and in which the One Health Poultry Hub was a partner, recently culminated in an international workshop in Entebbe, Uganda, hosted by the School of Health Sciences of Makerere University. Twenty-four researchers working in Africa, Asia and Latin America came together to present research and elaborate elements for a common antibiotic stewardship framework for agriculture within a unified One Health strategy.

Researchers from the One Health Poultry Hub brought results from recent social science research with farmers, feed dealers and veterinarians in Bangladesh into the discussion.

Poultry in Bangladesh

A specific feature of antibiotic use for poultry in Bangladesh is the prominent role of feed dealers. Besides feed, poultry farmers usually also source pharmaceutical products, including antibiotics, through feed dealers. Additionally, feed dealers often finance farmers’ poultry production by supplying feed and pharmaceutical products to them on credit, recouping their investment at the end of the production cycle when chickens (or eggs) are sold.

With limited access to few and distant veterinarians, farmers use antibiotics based on their prior experience or by following advice from their feed dealers – who not only profit from the sale of antibiotics but also want to make sure the farmers’ chickens that they invested in stay healthy. Their generous supply of antibiotics to farmers is thus as rational as it is risky for public health.

Increased knowledge among farmers and informal providers such as feed dealers is thus important, but it is unlikely to be sufficient to change practices of antibiotic use.

People need to be supported and have appropriate systems in place for producing poultry in ways that do not by default rely on the normalised overuse of antibiotics. Hence the need for an integrated antibiotic stewardship framework that builds on an understanding of farmers’ and providers’ economic and operational challenges for meeting their livelihoods requirements. Such a framework needs to create the right conditions for farmers to engage in sustainable production of safe and healthy poultry.

Insights from Uganda

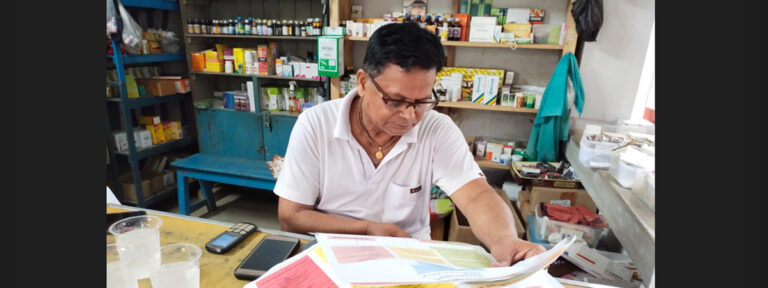

The School of Health Sciences at Makerere University organised field trips for workshop participants to learn about the perspectives of drug sellers in human and veterinary drug stores in Luweero and Mukono districts in Uganda. Several important observations were made.

Veterinary drug stores, for example, sell several supplementary vitamin products for poultry that contain antibiotics. Some of these products contain colistin, a last-resort antibiotic in human medicine whose ban in feed additives is urgently called for following the emergence of resistance in food animals.

While veterinary drug stores are concentrated in towns, more rural locations tend to only have smaller human drug stores. These do not stock veterinary products and are neither supposed to sell antibiotics (a service formally limited to pharmacies). They do, however, frequently sell antibiotics ‘under the counter’ (i.e., informally). Further, farmers do purchase these antibiotics to treat their livestock (a form of off-label ‘crossover-use’). Delegates reported that similar practices were commonly seen in other countries too.

These observations further highlight the urgent need for a unified One Health strategy for an antibiotic stewardship framework across agricultural and human use.

One Health strategy

An effective antibiotic stewardship framework thus needs to be multisectoral and follow a One Health strategy. It must address not only the reasons and circumstances that create the demand for antibiotics but also their supply and provision.

Antibiotic stewardship requires effective regulation that lowers barriers to adequate access while reducing inappropriate and excessive use. There also needs to be the political will and multisectoral coordination to make appropriate regulation workable internationally and at community level. We need to think about antibiotic stewardship systemically and should not decouple antibiotic stewardship from the understanding of how people in rural areas pursue their livelihoods.

Finally, we must work to create the conditions in which these livelihoods and agricultural practices are best pursued without overly relying on antibiotics.