The original “why did the chicken cross the road?” joke was published by New York magazine Knickerbocker back in 1847, and has been told in numerous iterations ever since. Now, 175 years after the invention of this ‘anti-joke’ (spoiler – the chicken crossed the road to get to the other side) chicken meat (referred to as ‘broiler’) production has become the dominant global meat source with over 100 million tons being produced each year. And I, as a researcher in broiler production systems, find myself repeatedly crossing a road in a busy market town east of Kolkata to talk to the many chicken dealers there.

We’re here to gain additional perspectives on the decisions taken by people working in broiler production – and to attempt to disentangle the role antibiotics play in production decisions. My current research is based within an ethnographic approach (ethnos = people, graphy = to write about); observing peoples’ practices and talking to them about their lives and experiences.

Producing chicken for meat on a commercial scale only emerged after the second world war as a response to shortages in other meat sources and following the 1948 ‘Chicken of Tomorrow’ competition in the USA. Back in the 1950s broiler birds took around 16 weeks to rear but over time genetic lines were selected for plumper breast meat and faster growth rates. Nowadays birds are slaughtered as early as 35 days, and many systems rely on antibiotics to support production. Unfortunately, antibiotic use results in the negative consequence of antibiotic resistance and efforts are being taken on global and national levels to try and understand how antibiotic use can be decreased (see for example the WHO’s Global Action Plan on AMR and India’s National Action Plan on AMR).

After arriving in the market town, we wait for a group of Gyr cattle to pass by before making our first street crossing to talk to a chicken dealer. Here we meet a young shop owner who has recently taken over his father’s shop. He talks about the negative impact of the 2020 Amphan cyclone and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on business and how he has started to make and sell incubators to compensate for his income loss (Figure 1).

He explains how prior to 2020 their shop had a steady business selling day-old chicks to independent broiler farmers. Nowadays, the shop sells few chicks as many of these farmers suffered heavy financial losses during these crises and consequently moved into contract broiler farming, where farmers face less financial risk. Contract companies work with broiler farmers to supply the necessary inputs for production – chicks, feed, and medicines, including antibiotics. In India, most chickens are reared in ‘open’ sheds made from a wood and wire frame covered by a roof. Birds are consequently exposed to both high temperature and humidity and pests and diseases in the surrounding environment, all of which increase risk during production. Consequently, antibiotics are routinely used by contract companies to reduce production risk; at the start of production (the brooding phase) to protect against yolk sac infections, in feed to promote growth rates, and whenever disease emerges. While some companies are investigating the use of antibiotic alternatives (like pro- and pre-biotics), these remain expensive compared to antibiotics and are not considered as effective at reducing risk in the most challenging production environments (for example during summer).

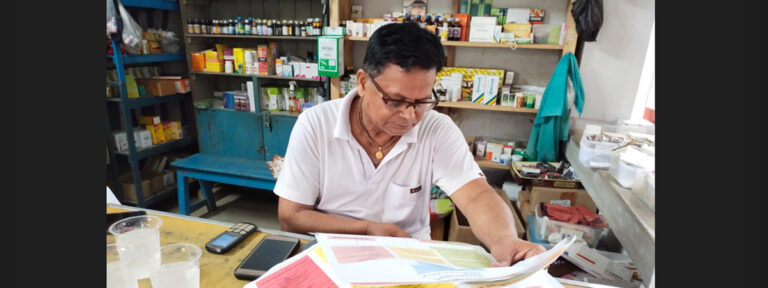

We cross the road again to visit another chicken dealer. Again, this dealer talked about the role of contract broiler companies, describing how they have taken over the market in the last decade and made it difficult for independent chicken dealers to operate. Now, most of this dealer’s business comes from small-scale backyard producers who buy small numbers of chicks (mainly local desi and cross-bred kuroiler breeds), feed, and medicines. While we talked, a customer came to the shop to ask advice about his chickens which were lethargic and not eating. This type of practice is known to be common in India, due to issues around the cost and access to formal veterinary services. The shop owner sold a small bottle containing an antibiotic mixture with instructions to give one drop orally twice a day for five day. This practice of ‘over the counter’ access to antibiotics without consultation with a qualified professional is known to be common in India, both within livestock and human treatment, and makes stewardship efforts to control antibiotic use particularly challenging, as it is difficult to monitor and control this practice. The inappropriate practices of contract companies present another type of challenge as these are driven by vested commercial interests.

Having completed our interviews for the day, we cross the road for a final time and head to the car. By now the mercury is reaching a heady 35 degrees C and the air conditioning inside provides a welcome relief for the journey back to Kolkata.